San Quentin resident Gerard Trent paroled after 53 years while facing triple life sentences

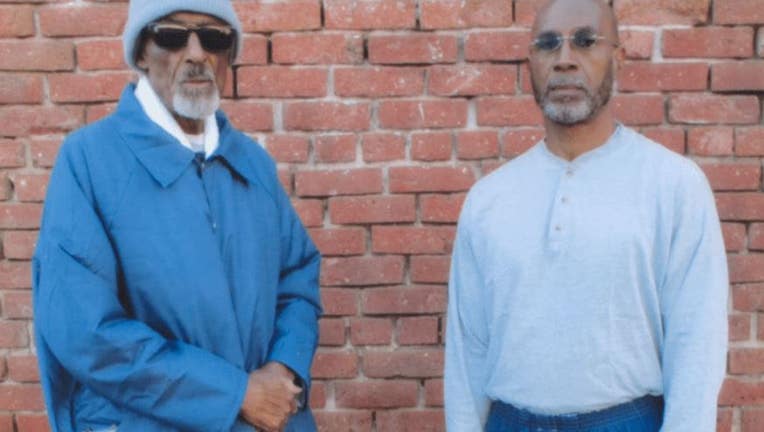

San Quentin residents Gerard Trent, left, and journalist Kevin Sawyer, right, at San Quentin Rehabilitation Center in San Quentin, Calif. (Kevin Sawyer/Bay City News)

SAN QUENTIN, Calif. - After serving 53 years of continuous incarceration in California prisons, Gerard Trent Jr., 78, paroled in October 2023 from San Quentin Rehabilitation Center.

Trent was an old-school "convict" from a bygone era of prison, when punishment was the purpose of incarceration and violence ruled the day.

"When I came into the system, people were going to test you, to see if you were up to the challenge," Trent said.

Highly respected by many of those who did time with him, Trent’s story is one of determination and perseverance. However, by his own admission, he did not complete his carceral journey alone.

"Others helped me and guided me," Trent said. "I had a lot of OGs in my corner. They taught me how to do my time."

Convicted in Los Angeles of triple murder in 1970, Trent repeatedly maintained his innocence for nearly six decades. He made more than a dozen appearances before past and present parole boards: Adult Authority, Community Release Board, Board of Prison Terms and finally, the Board of Parole Hearings.

According to Trent, Black prisoners did not always receive the same fair and impartial hearings as whites.

"Three times I didn’t show up at my Board hearings, in protest," he said.

"I know you have denied committing the murders," BPH commissioner Troy Taira said, according to the transcript from Trent’s May 2023 parole hearing.

"I didn’t commit no crime to get here in the first place," Trent said at his hearing, according to the transcript. "As you say in the record … I committed three murders, which I’m saying today, again for the 14th time, that I didn’t."

The third of nine siblings, Trent was born in Camden, Arkansas in 1945. His family moved in 1954 to Milwaukee, Wisconsin, where he came of age.

In January 1970, Trent arrived in California with his then common-law wife and her two boys.

"[She] and I was together a little over a year before we came to California," he said. "The boys was crazy about me."

Before 1970 ended, Trent was in jail, facing what he said are false charges of murder.

He said, "The Black man did it" is "a foundation for conviction" in the American criminal justice system.

"A person becomes a stepping stone for some prosecutors to advance their political careers," Trent said. "That’s not speculation and conjecture."

Like many convicts who have served excessively long sentences, Trent held onto a collection of family members’ obituaries, which include both of his parents. Letters brought bad news, and he was never allowed to attend a funeral.

"I don’t know if you heard," a 2016 letter from Trent’s sister-in-law begins about his brother. "I’m sad to have to tell you that Charlie died."

Seven California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation prisons held Trent for more than a half century – some more than once. The first time he arrived at San Quentin was in April 1971, four months before George Jackson, author of the book "Soledad Brother: The Prison Letters of George Jackson," who was killed along with three prison guards and two other prisoners.

"The unity of Blacks at San Quentin was unlike any in the state at that time in the 1970s," Trent said.

Over the decades, that unity changed. "I try not to think about it," Trent said of what so many Black men have been reduced to in prison.

"When I came to prison, you’d better not get caught sittin’ back on your bunk readin’ a ghetto novel," Trent said in a raspy voice, just above a whisper. "If you want entertainment, read Sun Tzu."

Trent has survived not only prison, but two bouts with cancer, in his vocal chords and prostate. Today all of his cancer is in remission, but he does suffer from other health issues due to his advancing age.

In his early years, Trent said surviving prison was based on how a convict carried himself.

"It had everything to do with respect," he said. "It wasn’t given. You had to earn it, and keep it."

He added, "That’s the most powerful tool anybody can carry in their toolbox in prison. And it has to extend beyond your own race."

According to Trent, Los Angeles County District Attorney George Gascon has his conviction integrity unit reviewing state improprieties involved in his arrest and subsequent conviction.

"Mr. Trent was 25 at the time of the murders," said Taira, the BPH commissioner. "He has consistently denied the murders."

Trent said he wants to prevent other young men from following the steps that made him a target for prison, recalling the four years he spent in a reformatory when he was 17.

In his cell, Trent had numerous files containing laudatory documents, certificates of achievement, self-help programs and trades he completed, and letters of support. One letter, written by the attorney who worked on his appeal in the early 1970s, wrote that Trent’s case stayed on his mind over the years because he did not believe he was guilty.

Nevertheless, Trent continued to accumulate documentation of his reform, 35 years before "rehabilitation" was added to what was then the CDC.

In the 1970s, Trent was a mentor in San Quentin’s youth program, SQUIRES. He still carried the card in his wallet. Thoughts of running a similar program for youth outside is where he sees himself working in the future.

"The key to everything I want to do hinges on [me] fully being exonerated," Trent said. "I want to intercept some of these kids before they get to prison."

"We don’t grant or deny parole on the basis of whether somebody admits to the crime," Taira said at the BPH hearing.

Trent disagreed because he first became eligible for parole in 1975. That’s because his three sentences of seven years to life for three counts of murder were run concurrently.

"I think the judge was trying to help me out," he said.

Fifty-three years later, Taira said at the hearing, "We did find his denial to be plausible, although, you know, that is – we’re not in a position to relitigate the case."

"The time is 10:55 a.m.," BPH deputy commissioner Edward Taylor said at the end of the hearing. "We are off record."

That’s how 53 years inside prison ended for Trent. He paroled to Los Angeles.

This story was originally published by LocalNewsMatters.org, the nonprofit affiliate of Bay City News. Find it here: