Emergency warning systems present patchwork of problems

Emergency warning systems in NorCal present patchwork of problems

When there’s a wildfire, earthquake or power shutoff, people expect an emergency alert, but 2 Investigates found that only a small fraction of residents in most Bay Area counties have signed up for those warning messages, and because every county has its own policies, procedures and software, even those who opt in won’t always be covered.

SACRAMENTO, Calif. - When there’s a wildfire, earthquake or power shutoff, people expect an emergency alert, but 2 Investigates found that only a small fraction of residents in most Bay Area counties have signed up for those warning messages, and because every county has its own policies, procedures, and software, even those who opt in won’t always be covered.

The patchwork of emergency alert systems in Northern California makes staying informed and connected with the right emergency notifications extremely difficult and confusing, especially if a person lives in one county and works in another.

Across the Bay Area, most counties have less than 15% of people opting-in, according to data reviewed by 2 Investigates, but some counties have far fewer registrants.

"It's understandable because of the confusing environment a lot of people aren't sure what alerting system they're signed up for because they logically enough assumed there's one alerting system and there's more than one,’’ said Woody Baker-Cohn, Marin County’s emergency services coordinator.

In Contra Costa County, just 7% of residents are signed up to receive alerts, but even those people aren’t guaranteed a timely disaster warning, according to the terms of service, which says you "shouldn’t rely" on the alerts, it "may provide false alerts" or "fail to warn" in an emergency.

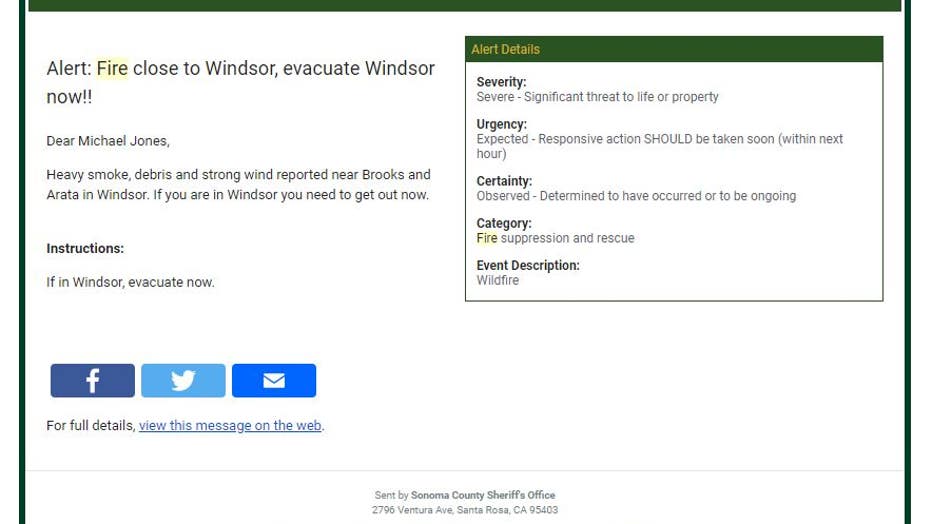

A 2 Investigates review found that in Sonoma County -- where there have been years of deadly and destructive wildfires -- just about 12% of residents are registered to receive emergency alerts.

But KTVU wanted to check emergency alert systems ourselves. A year ago, KTVU investigative reporter Brooks Jarosz signed up to receive alerts from every county, city, and agency in the Bay Area. That resulted in thousands of warnings, but because of technology flaws and piecemeal procedures, there were dozens of alerts that were distributed, but never landed in the reporter’s email inbox or to his smartphone.

"When we talk about a warning system, it's not just something you just go out and buy,’’ said Art Botterell, a former state emergency services coordinator.

Botterell said the biggest problem is relying on technology in the private sector to fix the state’s disaster communications.

"I think that's a result of a failure of responsibility. It's piecemealed throughout the state because nobody made any effort to set standards throughout the state or to be consistent throughout the state,” he said. “As a result, we got whatever various sales people sold to various jurisdictions at various points in time."

During a recent test of San Francisco’s warning system, alerts were delayed by nearly an hour.

In Santa Rosa, a warning about toxic smoke from a fire was delayed 30 minutes for Spanish speakers because a translator was not available.

And the new ShakeAlert earthquake system also saw glitches when it was activated last month on the 30th anniversary of the Loma Prieta earthquake.

Two years ago, the deadly North Bay fires whipped through parts of Santa Rosa and officials said multiple alert systems were activated and alerts went out.

But, for those who weren’t signed up, or if cell towers were down, the warnings never came. That led to new efforts to get people signed up to receive warnings, including the city importing information through water bills.

During last year’s Camp Fire in Butte County, the deadliest and most destructive wildfire in California history, the mayor admitted officials never successfully activated a free government notification system.

"(The alerts) were too little and we lost the ability to do them,’’ said Paradise Mayor Judy Jones. "You need to have a redundant system."

A Butte County Grand Jury report blasted emergency managers for relying on a single warning system.

"There has to be multiple ways that you can get information to people." the mayor said.

One of the most basic and widespread systems in place is Nixle, which sends alert messages to registrants based upon their zip code. Many cities and county agencies use Nixle to send messages about everything from community events to fire warnings. Nixle cannot pinpoint evacuation or danger zones, and that’s one reason officials are using more advanced technology tools.

Nixle’s parent company, Everbridge, and other competitors like OnSolve, have developed ways to target specific addresses or areas on a map. People who sign up are asked to put in addresses of importance like their home, workplace, school, or gym.

Baker-Cohn uses the system often and said the system is so accurate, it can pinpoint a single house. He’s also able to send out notifications on Nixle, through social media, and by reverse 911 lookups in just one click.

CLICK HERE to see a list of links to connect and receive alerts in a specific Bay Area city or county.

But the biggest hurdle, again, is getting people to sign-up, which has proven difficult. To battle that problem, there is a system developed by the federal government touted as the Integrated Public Alert and Warning System or IPAWS.

The system was developed in 2006 by the federal government following an executive order by President George W. Bush. The order required an “effective, reliable, integrated, flexible and comprehensive system to alert and warn the American people.”

IPAWS can be used by local emergency managers to send warnings that interrupt television and radio broadcasts, and to wireless phones in specific areas. The system is also used for Amber Alerts, messages from the president, and to warn people about natural disasters -- like wildfires.

"Your phone goes crazy making a loud noise until you come over and tell it to proactively stop,’’ said Bill Boutin, a Sonoma County resident.

The system uses GPS to pinpoint an exact location.

But nothing will work correctly if cellular towers are down and data services go out. At one point during the PG&E power shutoffs in October, 60% of cellular towers were down in Marin County alone. And across the state, more than 700 towers weren’t working. That’s despite telecom companies promising regulators they had plans to keep things up and running.

New state laws are aimed at improving notifications. One required the California Office of Emergency Services to develop state guidelines.

"It's a starting point but certainly we're constantly looking at ways to improve," said Brian Ferguson, a spokesman for Cal OES. "What we want to do is learn from the past. It seems like there were gaps in this tapestry you described and the emphasis now is identifying and closing those gaps to keep people safe."

Still, there are critics.

"People have to understand that this has not been solved,’’ said Botterell. “This is not a ‘nothing to see here’ sort of a problem. This is a problem area that's going to take political attention, it's going to take investment (and) it's going to be the creation of new professional standards of practice."