Professional Richmond basketball player is Bay Area legend

Professional basketball player talks about dribbling basketball for a living

Jovan Harris is one of the few thousand pro athletes from the United States who has earned a living dribbling a basketball.

RICHMOND, Calif. - There’s a little less than six minutes left in the game and the Mexican national team is losing.

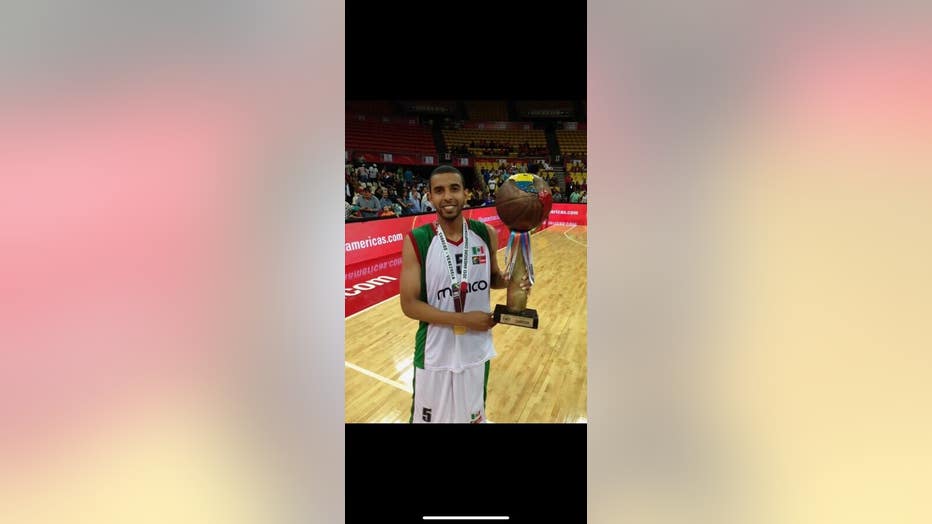

NBA champion J.J. Berea is moments away from leading Puerto Rico to an international tournament victory. But East Bay native Jovan Harris stepped up and refused to go down without a fight. He scored 16 points in the fourth quarter at the FIBA Americas Championship for Men and returned to North America with a gold medal.

"One minute I’m in Richmond, then I’m representing an entire country on a basketball court," said Harris, who is Mexican-American. "That’s probably one of the proudest moments in my career."

Harris is one of the few thousand pro athletes from the United States who has earned a living dribbling a basketball.

When most people think of professional basketball they think of the National Basketball Association, which has 30 teams with about 15 spots on each roster. However, there are pro players in the U.S. that aren’t signed to an NBA contract and choose to continue their playing career in Mexico, Canada, or overseas. And Harris is one of those players.

Basketball began in Richmond

While the 6 '4 left-handed hooper didn’t play in the NBA, he has dedicated his career to playing professional basketball. Harris’ path to achieving his dreams may seem unconventional by mainstream standards, but as he reflects on his career he is proud of everything he’s accomplished.

His roots are deep in Richmond, where violence and street life are akin to neighborhood culture, and is now living his life with international success as an athlete who is getting paid to do what he loves.

"Since I was a kid, I just wanted to hoop. I wasn’t interested in working a nine to five," Harris said. "Basketball has paid for everything I own. The car I drive, my mother’s mortgage, everything I have is because of that little round ball."

Harris’s journey started in Richmond. As a 13-year-old student at the now defunct Adams Middle school in the mid-late 1990s, he developed an authentic passion for the game. He schooled his classmates on the court and even his peers realized he had size and skills that were beyond his age. By the time he got to high school, Harris realized he might have a shot at playing professional basketball one day.

"I would play with kids two, three years older than me and they wouldn’t believe me when I told them I was only 13," Harris said.

Javon and Franco Harris are brothers who are both basketball stars in their own right.

Pro-Am success

He was a freshman when he got his first chance to play against seasoned college and pro basketball players at the San Francisco Bay Area Pro-Am league. The SF Pro-Am is a summer event at Kezar Stadium that has dozens of high-level basketball players from around the Bay Area and elsewhere compete in a basketball showcase. It’s been around for the last 40 years and has seen Bay Area basketball legends such as Jason Kidd, Gary Payton, and Steph Curry participate.

Harris was invited by school alumni to watch a game. When one of the teams only had four available players at the game he attended, Harris was asked to come out of the stands and be the fifth player on a team made up of Division I college players.

"I had my hoop shoes with me and back then we used to wear our basketball shorts under our jeans, so I just laced my shoes up and went to play," Harris said.

Twenty-seven years later, Harris is considered a SF Bay Area Pro-Am legend.

Since his debut in 1996, he’s won three league championships and earned two MVP awards while competing with and beating teams that boasted NBA talent.

"I played against Matt Barnes, Tyreke Evans, Jeremy Lin and other guys that played in the League," Harris said. "Every time I step on the court I always feel like I can compete with anyone."

Javon Harris is one of the few thousand pro athletes from the United States who has earned a living dribbling a basketball.

Life as a student-athlete

That same competitive drive turned Harris into one of the best high school players in the region. He developed his skills alongside other teammates that went on to play college basketball, including 14-year NBA veteran Drew Gooden. His senior year, he helped lead his high school to the state championship game and a near perfect record.

The El Cerrito High School alumni went on to star at St. Mary’s College in Moraga where he was one of the leading scorers in the West Coast Conference and an all-league honorable mention his sophomore year. Despite Harris’s on the court success, the team did not win many games his first two seasons. In addition to losing, the transition from the public school system to a private institution was a struggle for Harris.

"It was a culture shock," Harris said. "I learned quickly that private schools are different and you really have to be a student-athlete first. I never needed a tutor until I got to college."

Players aspiring to have a career after college know that it helps to be on winning teams. After two seasons of individual success in Moraga, Harris transferred to Contra Costa College and sat out one season before going to the University of San Francisco.

He continued to play well and got off to a great start at USF. However, a mid-season clash with the head coach derailed his playing time and he fell out of the playing rotation. When he started to spend more time on the bench than in the game, his frustration boiled over.

One game, Harris and the head coach got into a verbal altercation and Harris was sent back to the locker room. As a result, he was suspended for two of the biggest games of the season. While the ending to Harris’s playing days in college wasn’t a storybook ending, he learned a valuable life lesson.

"I knew what it felt like to be the star on my team," Harris said. "But I also learned how to contribute as a role player."

Harris kept his vision of playing pro basketball alive by playing in a few semi-professional leagues for a couple of years after college.

In 2007, he drove down to the San Joaquin Valley and landed a spot on the Bakersfield Jam, a team in the NBA's Development League.

The D-League, now referred to as the G-League after a sponsorship deal with Gatorade, is the NBA version of a farm system that prepares players, coaches and staff for the NBA. Harris’s scoring, ball-handling, and size for his position impressed scouts and coaches during a workout for the team.

He played one season for the Jam before being traded to the NBA affiliate team in Iowa where he played for current Toronto Raptors head coach and NBA champion Nick Nurse.

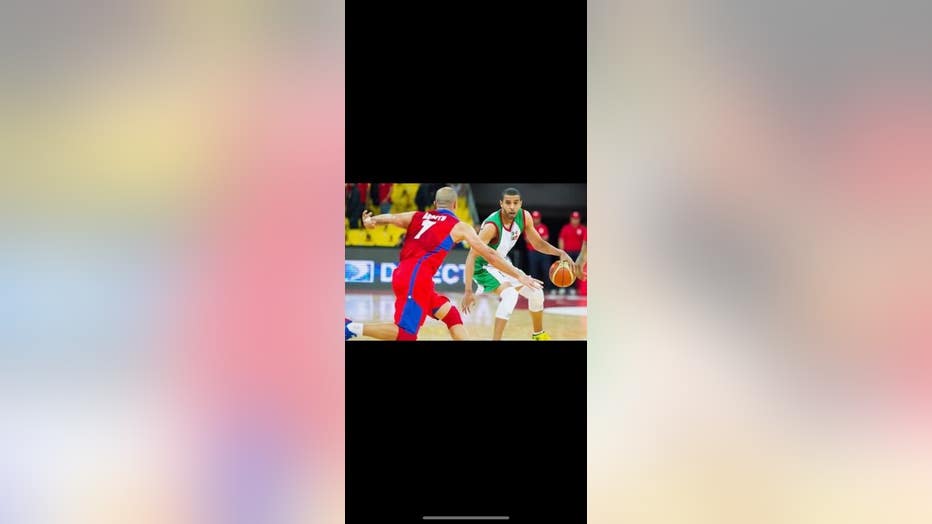

Javon Harris (R) is from Richmond and a San Francisco Proo-Am legend.

Playing basketball across the border

While Harris was playing in the D-League, Harris’s younger brother, Franco, was just starting his pro basketball career across the border in Tijuana. After Harris played a couple of seasons in the NBA’s minor league, Franco reached out to his brother about an opportunity.

"My brother called me and was like, they’re asking about you in Mexico," Harris said. You should come check it out."

Franco is an accomplished basketball player in his own right. He played at Boise State after transferring from Diablo Valley College where he was recently inducted into the school’s athletics hall of fame. He has 15 seasons under his belt as a pro basketball player in Mexico and is currently preparing for the upcoming season.

"I just felt like Jovan was being overlooked and I thought he’d be well received by the fans and culture," Franco said. "His game and career blossomed even more after the D-League."

Harris left the D-League and the states for Mexico and signed to play in the country’s premier basketball league, Liga Nacional de Baloncesto Professional. He’s earned the respect of the Mexican sports press and became a fan favorite as one of the best players in the league.

"It was a blessing to play with my brother," Franco said. "He became the top Mexican-American player in the entire country."

Overcoming injury and World Cup disappointment

As one of the best players in the country, Harris played his way onto the national basketball team. Despite being paid to play the game he dedicated his life to, success in Mexico didn’t come without struggle. In 2013, Harris tore his ACL and couldn’t walk five months before playing at the FIBA Americas Championship for Men.

"I worked really hard to get back on the court and play again, Harris said. "I wanted to play for the national team and continue my playing career, but I knew teams weren’t going to pay an injured player."

Harris did recover and signed a new contract.

He also lifted the country to a gold medal victory with his epic fourth quarter performance. However, disappointment would set in again when he wasn’t invited back to play on the national team the following year. He had his sights set on playing in the 2014 World Cup in Spain, where some of international basketball’s biggest stars take center stage, including Team U.S.A that features cream of the crop NBA players.

"I thought they’d ask me to play on the national team again after how I played the year before," said Harris. "We didn’t just qualify for the World Cup, we won the tournament."

Harris admits the experience wasn’t flawless. It was a struggle to be away from family and friends for half of the year. The league was also still in its infancy, barely a decade old. At times, it lacked the overall organization of more established sports leagues in North America.

Despite feeling slighted by the Mexican national team and adjusting to another culture away from family and friends, Harris continued to play in the LNBP until 2020, but returned home during the pandemic. Playing basketball is the only job he’s ever had. He says he’s in a comfortable position right now and surveying his next move.

Javon Harris (R) often plays basketball in Mexico.

Sticking close to the game

Harris is a classic hooper, a gym-rat whose passion is fueled by competing on a basketball court. At age 42, when Harris isn’t with his one-year-old daughter, he’s still in the gym working on his craft.

He still trains every morning and plays in night leagues to stay in shape. Harris says the whole pandemic shutdown disrupted his life and career. He’s considered going back to play in Mexico this upcoming season, but has more to think about now with a young family.

Harris is also thinking about what he wants to do when he decides his playing days are over.

He’s thought about coaching or conducting private training lessons and workouts to stay close to the game. He’s confident that what he’s learned along his career path can benefit the next generation of players.

"There’s not many people walking around that can say they’ve won a gold medal," Harris said. "I’m sure you won’t find me too far away from the game. Basketball is the only life I know. I really don’t know what else to do."

JT Cunningham III is a writer at KTVU. Contact him at john.cunningham@fox.com.