The price of survival: What's the future of SF's indie performance spaces?

(Photo courtesy of Bottom of the Hill)

SAN FRANCISCO - The week of Sept. 14 marked an unlikely milestone for San

Francisco: It was the week many of the city's businesses reopened to the public (after several starts and stops during the summer) and it marked six months to the day since Mayor London Breed first ordered the city be locked down.

That order -- given to prevent the spread of COVID-19 -- was

expected to last no more than a few weeks; maybe a month, at most.

The week of the 14th was also when worldwide coronavirus cases

topped 30 million. Despite the city's impressive efforts, the virus is still here.

For local artists like playwright Marissa Skudlarek -- whose

adaptation of Edmond Rostand's "Cyrano" was scheduled to open at Cutting Ball Theater in April -- the lockdown put the brakes on projects already in motion.

"We started rehearsing 'Cyrano' in early March," she said, "so we

got about a week of rehearsals in before we had to shut down due to the pandemic." She says she was "thrilled and invigorated" to finally see the play on its feet, but couldn't shake the doubt that came with reading breaking headlines.

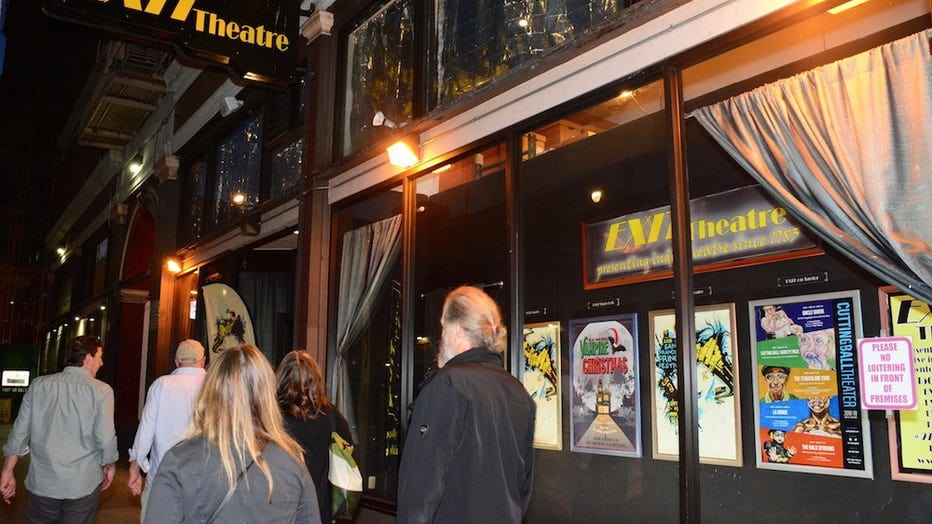

(Photo by Colin Hussey, courtesy of the EXIT Theatre)

At that point, the lockdown itself came as something of a relief.

"In those horrible early days of the pandemic, it caused me great

mental strain to have to publicly promote 'Cyrano' while privately suspecting that it wouldn't make it to opening night."

She wasn't the only one.

The pandemic has damaged the live performance industry worse than most others, save for education. While restaurants, gyms, and salons have also felt the sting, they've been able to adapt by moving into delivery, outdoor, and private online appointments.

Performing arts don't really have that luxury. Their entire

infrastructure -- both artistically and economically -- is based around the idea of patrons paying money to see a live performance. As Remi X of S.F. synth-pop trio Vice Reine said, the ability to "feel or feed off of the audience's energy" is key to having an audience in the first place.

"For me, the best part of going to shows was not only hearing the

music or seeing the band, but getting to dance and interact in a crowd," she said. "There's this huge social aspect you really just can't replicate."

With everyone from The Rolling Stones to Taylor Swift forced to

cancel all of their shows for the year, the mainstream concert industry is expected to lose upward of $9 billion. But those kinds of marquee acts have lucrative contracts to fall back on. What's more, the major promoters and venue owners (AEG, LiveNation, Goldenvoice, etc.) are able to spend around $150 million a month without hurting their bottom line.

Independent venues have no such golden parachute, forcing many -- The Uptown and The Stork Club in Oakland, Slim's in San Francisco -- to close their doors for good. (Slim's is scheduled to be replaced by the YOLO "ultra lounge" by Pimp Group.) And that's just a fraction of the nearly 5,000 San Francisco businesses that have closed as a result of the pandemic.

(Photo courtesy of PianoFight)

With the cloud of permanent closure hovering over the Bay Area's

favorite performance spots, many San Francisco locations have united for the sake of self-preservation.

This led to the creation of the Independent Venue Alliance (IVA),

which currently lists 24 venues as members. The alliance exists to "give a unified voice" to non-corporate performance spaces and "amplify [their] shared cause, not only through this current crisis but beyond to the crisis that was already decimating independent venues across the nation and the world."

Membership requires that each business be "a non-publicly traded

business with a brick & mortar building in San Francisco."

According to Lynn Schwarz -- an IVA committee member and

booker/co-owner of Bottom of the Hill -- the alliance actively encourages venues catering to diverse backgrounds (she showed a seven-question application for potential venues, asking, among other things, if a venue is "more than 50 percent BIPOC, LGBTQ+, women, or persons with disabilities -owned") and Schwarz herself is "eagerly awaiting responses" from San Francisco-based jazz, blues, hip-hop, Latinx, and dance clubs that have been

invited to join.

All noble intentions, but they don't quite explain how the

alliance or the venues within will financially sustain themselves through the coronavirus pandemic.

In addition to selling branded merchandise, many of the venues

have started Patreon accounts, GoFundMe pages, and even direct-payment donation links. But those can only help so much. (The Uptown in Oakland had started a GoFundMe page nearly a full month before its owners announced its closure.)

In August, The Chapel in the Mission became the first IVA venue to open its doors to a live audience. The drive-in show - presented by (((folkYEAH!))) - was put on as a benefit concert for the alliance.

Audiences remained in their cars, as they watched the Red Room

Orchestra play its David Lynch tribute for the duration of the show. But admission wasn't cheap, ranging from $250-$450. With the pandemic putting the squeeze on everyone's finances, that kind of pricing doesn't exactly invite the average patron to take part.

Streaming is an option, but not everyone has the resources of

Burning Man or Hardly Strictly Bluegrass, which both moved online this year.

Still, some indie venues are streaming shows for free, with the option for viewers to donate at any time, but that just pronounces the money problem all the more.

The possibility of a live audience brings with it a host of safety

and environmental concerns. Even Bay Area restaurants and salons that have successfully moved outdoors find themselves at the mercy of seasonal cold weather and a month of wildfire smog.

When the topic is broached of opening his location to an in-person

audience, DNA Lounge owner Jamie Zawinski rejects the "completely, utterly impractical" idea.

"For us to have a small enough audience, plus enough staff to

ensure that they are behaving safely, would mean the ticket price would have to be so ridiculously high that nobody would pay it," Zawinski said.

The DNA Lounge -- which has always livestreamed shows from its two stages for free on its official website -- has averaged three-five weekly shows since the pandemic began, including Vice Reine's monthly Star Crash electronic dance party.

No matter how much Zawinski misses the audiences, he can't see the DNA Lounge following in The Chapel's lead with the (((folkYEAH!))) show.

"We are in the business of putting on sweaty concerts that cost

$8-$20," he says. "Asking us to 'pivot' to seated dinner theater at

$1,000-a-head is just not realistic. The best case scenario is that it barely covers its own costs. The entertainment venues on this block alone used to provide employment to hundreds of people on a busy night. That kind of mini-street fair won't be able to replace that, let alone pay the rent on all of those empty buildings."

Rob Ready, the co-founder and artistic director of PianoFight --

which has also livestreamed free shows and is one of the few indie venues to expand during lockdown -- agrees with Zawinski about performers in the venue ("Very comfortable having performers; not comfortable with audiences"), but is a bit more forgiving of The Chapel's high-priced approach.

"Generally speaking, art and live performance [are] pretty

undervalued in this country," he says. "It's hard to get a turkey sandwich for what it costs to see most indie live shows. Given that, and the fact that it costs a lot more to create the safety infrastructure to hold an event right now, ticket prices should be high. And folks, I think, will be generally happy to pay them if a.) it means the event is run responsibly and b.) they get to see a live show!"

Both Ready and his PianoFight colleagues are supporters of live

performance in all of its myriad forms. PF's two stages (not counting an additional cabaret stage across from the bar) have made it a go-to destination for live theater in San Francisco. Although he's glad the location is part of the IVA, he wishes the alliance would give proper theater more attention.

"As we do in the theater community, we are always pushing to build a bigger tent," he says. "The Independent Venue Alliance is geared towards music venues, with some exceptions. The same way we've pushed [Bay Area theater resource] Theatre Bay Area to include drag, improv, and sketch comedy in their awards, we're advocating that the IVA include non-music related venues in its membership."

Indeed, of the IVA's 24 listed venues, very few (like PianoFight

and the DNA) are truly known for moving beyond music to include more eclectic programming. It speaks to a larger problem of traditional theater not having much of a voice in the discussion of pandemic-stricken art forms.

Although millions of people have watched "Hamilton" on Disney+,

independent companies and troupes are stuck with streaming archive videos of old productions (usually marked by poor sound and video), experimenting with socially distant outdoor performances (such as with Oakland's Neighborhood Stories), or free readings of new scripts.

Skudlarek knows the advantages and disadvantages of "Zoom theater" all too well. Of the advantages, she says, "I liked being able to text with friends about the show while it was happening, and chair-dancing to the pre-show and intermission music - two things I'd never do at a live in-person show. I also love being able to see actors' faces and reactions close up, which can feel more intimate and involving than seeing a show from far away

in a large venue."

Of the disadvantages: "Theater is about reaction, but it's also

about interaction, and even with the very clever direction and staging of [a recent live-streamed] show, there were times when I wished I could see two faces or two bodies on a single screen."

Fellow playwright Bridgette Dutta Portman expresses similar

sentiments.

"I've had a couple of readings and productions done online now and I think they mostly work well," she said. "There was one in particular: my play 'Ageless,' that is set in the future and is partly about technology, so I think that play actually lends itself to a digital format. One thing I miss is audience reaction. Laughing, gasping, etc. We can do that with emojis, but it's not quite the same."

Live performance needs an audience, one that streaming can't

match. (And reports of "livestream fatigue" don't help matters either.)

The other thing they need is money. In addition to the

aforementioned donation links, several venues sought out federal funding to stay afloat. Not all have succeeded in getting them.

The IVA has made it their chief priority to secure that protection

for small businesses. Like countless indie venues around the country, the IVA are vocal proponents of two federal acts designed to provide that very support: the Save Our Stages Act (S.4258 / H.R.7806), introduced by Sens. John Cornyn, R-Texas, and Amy Klobuchar, D-Minn. and Reps. Peter Welch, D-Ill. and Roger Williams, R-Texas, and the RESTART Act (S.3814 / H.R.7481), introduced by Sens. Michael Bennet, D-Colo., and Todd Young, R-Ind., and Reps. Jared Golden, D-Maine, and Mike Kelly (R-Penn.).

These acts aim to "provide vital support for independent venues

that have lost nearly 100 percent of their revenue since the pandemic began in March."

On Sept. 1, numerous indie locations around the U.S. took part in

the "Red Alert for RESTART" demonstration, which saw the fronts of the venues bathed in red light to draw attention to the acts and their necessity.

Needless to say, time is a crucial factor. Whereas Hollywood has

multiple revenue streams at its disposal (even those who didn't contribute to "Tenet's" $20 million opening, still have the option of first-run films at home), no live performance venue has made any plans to reopen its doors anytime soon -- even as San Francisco promises to restore limited museum visits and indoor dining by the start of October.

The idea of having an all-digital "live" audience -- as seen in

the Emmy Awards and recent pro wrestling broadcasts -- doesn't seem financially or technically feasible. Nor do they have the power of the NFL to impose massive fines on players and audience members who break social distancing and face mask guidelines.

What's more, the current presidential administration is doggedly

determined to eliminate funding to arts and humanities, making the passage of the proposed legislation all the more an uphill battle.

But what other options are there? San Francisco has long been a

mecca for creatives and outsiders, but it's still in the midst of an

expensive second tech boom. With all the talk of COVID-19 finally bursting that bubble, the city remains prohibitively expensive for the non-oligarch. And the pandemic has made it all the more difficult for artists of all stripes to take full advantage of their chosen format.

As Zawinski bluntly puts it, "We all need material support, by

which I mean money - from city, state and federal sources. That's it. It's obvious, and it's not complicated. Without that, there are no more independent venues by the end of the pandemic."

Yet, even in the midst of industry collapse, there is optimism to

be found. On Sept. 25, San Francisco implemented a permit program for outdoor entertainment, opening the door for open-air performances.

And although Lynn Schwarz -- who fielded questions between working two side jobs -- is realistic about the need for money, she and her fellow venue owners have used lockdown time to carry out a lot of necessary maintenance on their locations. Furthermore, she sees the growth of the IVA as an encouraging show of solidarity for San Francisco's independent venues.

"I do indeed wholeheartedly encourage any and all venues who meet our criteria to apply," Schwarz said. "Or to apply even if they come close to meeting our criteria! ... The whole reason we exist is to prop up any and all smaller live music venues that need help!"

Ready agrees. "One silver lining of this pandemic has been that

event organizers, venues, and artists are talking to each other and

organizing in a way that I've never seen before," he said. "It's exciting and necessary. So, folks who are feeling alone, scared, or lost out there should take heart in the fact that we all feel that way, we're all in the same boat, and truly none of us are alone in this."

Christina Augello is the founder and artistic director of the EXIT

Theatre, home of the renowned San Francisco Fringe Festival and the unofficial heart of the S.F. independent theater scene. SF Fringe has been postponed one year, but the EXIT still hosted an online event called the "Fringe Sneak Peak," in which several artists who would have performed this year still had the opportunity to show their material.

Augello was asked if live performance still has a future in San

Francisco. "There are a lot of diverse arts and venues out there," she said.

"We are fortunate to have had such an abundance in the Bay Area. ... As to the future, no one seems to know what will happen, and it's a wait-and-see time. With any luck many of us will rise from the ashes."

* Charles Lewis III is a San Francisco-born journalist, theater

artist and arts critic. He's online at TheThinkingMansIdiot.wordpress.com.

This story was first published on LocalNewsMatters.org, an affiliated nonprofit site supported by Bay City News Foundation.