3 workers killed at San Leandro company; Cal-OSHA has no power to shut down

3 workers killed at San Leandro company; Cal-OSHA has no power to shut down

Three workers in the last eight years have died at a family-owned San Leandro metal recycling business, and the company has been fined for more than 60 safety violations as far back as the 1990s.

SAN LEANDRO, Calif. - Three workers in the last eight years have been killed at a family-owned metal scrap recycling business, and the San Leandro company has been fined for more than 60 safety violations as far back as the 1990s – possibly the worst safety record of any similar company in the last 10 years in California, a review of federal data shows.

Despite the deaths and injuries at Alco Iron & Metal, the state has no real power to shut this company, or any company, down completely.

Inspectors with California’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration, or Cal-OSHA, have done their part by citing and fining Alco. But the company has regularly been able to appeal the violations and pay a lesser amount, as is their right under state law.

"So you have sort of a perfect storm of understaffing, of cuts, and refunding employers, including irresponsible employers like Alco," said Garrett Brown, a former field inspector for Cal-OSHA, who personally cited Alco 17 times during his career and now has made a hobby of being an unofficial agency watchdog.

Three deaths in eight years

KTVU obtained video of Luis Guerrero being crushed by a forklift at Alco Iron & Steel in San Leandro. Jan. 8, 2025

The most recent death at Alco Iron & Metal happened nearly four months ago, on Jan. 8.

Mechanic Luis Fernando Guerrero Tlatenchi, 41, of Castro Valley, who goes by the surname Guerrero, was killed after a forklift fell on him.

KTVU obtained exclusive video showing what happened that day.

And while there is no sound in the video, it is still difficult to watch.

The video shows Guerreo walking to the back of the broken forklift, and the machine taking a swift nosedive to the ground, trapping him underneath. He is seen flat on his back, as employees rush to his aid.

"He was funny. He was very professional," former Alco co-worker Cesar Zamora said of his friend, who leaves behind a widow and four children. "He was always smart when it came to mechanic work. He knew his thing."

Another worker, Ray Alfaro, was killed on March 31, 2022, at Alco’s yard in Stockton, when he was crushed by 4,000 pounds of bundled wire that were stacked on top of each other and fell on top of him.

Cal-OSHA fined Alco $18,000 after Alfaro’s death, but Alco contested that. The case is still pending, and the fine is still unpaid, three years later, records show.

And on June 30, 2017, Alberto Anaya was killed when the wheels of a large machine, called a screw conveyor, caught a crack in the concrete floor and the frame collapsed on top of him.

OSHA fined the company $45,000 for Anaya’s death.

Alco appealed and paid only $7,000 after Administrative Law Judge Kevin J. Reedy ordered that the agreement was OK, records show.

Deaths are ‘shocking’

Garrett Brown, a former Cal-OSHA inspector.

"Three deaths in just a number of years is shocking," Oakland's Worksafe Executive Director Stephen Knight said. "This is an unacceptable level of clearly unsafe conditions. Employers tend to blame their workers when something happens. And you will see media coverage that will describe a freak accident of a worker getting caught in a wood chipper or crushed in a trench collapse. But these are completely foreseeable and avoidable situations that should never happen."

Brown, who cited Alco for "willful" violations in the late 1990s, went even further.

"It’s very unusual," Brown said. "And frankly, shows a total cavalier attitude towards the health and safety of their employees… These people have been bad actors for 30 years. In the 20-odd years that I worked in the field, this is clearly the employer with the worst record."

Comparing other metal recyclers

There is no central database that specifically compares the death or injury rate of companies in the metal recycling business.

So, KTVU pored through federal OSHA records from 2015 to 2025 to compare Alco’s citation and death rate to nine other metal scrap recycling companies in California.

Alco had the highest death rate in the last decade of any metal scrap recycler of those reviewed, a review of OSHA data shows.

In fact, only one other metal recycling company has had a single death over the last decade: Sims Group USA, which has 4,000 employees, 20 times more than Alco.

KTVU also compared Alco’s history to that of Schnitzer Steel in Oakland, perhaps the most well-known metal scrap company in the Bay Area, and a company with 3,000 employees, 15 times more than Alco.

In addition to the three employees being killed, Cal-OSHA records show 64 citations resulting from 22 state inspections dating back to 1991 at Alco. Twelve of those violations were "serious" and six were "willful."

In the same time period, Schnitzer had 22 citations and zero deaths.

What are Cal-OSHA’s powers?

Stephen Knight, executive director of Worksafe in Oakland.

Cal-OSHA only has the power to shut down portions of a company, like a particular machine or zone.

But the state agency does not have the power to close companies completely. When companies fix the problem, they are allowed to reopen and go back to work.

"California's job is not to shut down companies, but to ensure a safe workplace," Knight said. "And so, they will inspect if they find violations. They're often quite small fines. And generally, then there's a process where employers appeal. And the fines often get reduced, routinely by 90%, because the employer will fix the hazard and then pay a small percentage of the fee. And then the case is over."

No one from Cal-OSHA who currently works at the agency agreed to be interviewed about this company, although spokespeople did answer factual questions by email.

What the company says

Alco Iron & Metal in San Leandro has been in business since 1953.

Alco Iron & Metal has been recycling, fabricating and selling metal products to customers in the United States and internationally since 1953, according to its website.

Alco has five facilities in San Leandro, two in Vallejo, Stockton and San Jose. The company has approximately 200 employees.

KTVU reached out to Alco Iron & Metal to speak to its two owners, brothers Kem and Kevin Kantor.

At first, Alco executives said someone from the company would sit down to answer questions.

But the company's executives changed their minds "due to the ongoing investigations in the last two incidents," according to their COO Michael Bercovich via email.

Instead, Alco provided a six-paragraph email to KTVU, which said, in part, that Alco has "always been a safe and family-oriented place to work."

"Alco truly is a family, and all of us watch out and care for each other," the statement read. "Alco prides itself on a robust safety training program and a culture where all management and employees buy into its importance."

The Alco statement said that "each of our employees is required to go through a rigorous training orientation when they are hired and that training is refreshed on a regular basis during their employment."

The company also said that "Alco is devastated by the three incidents you raise. In each instance, Alco cooperated fully with the workplace safety investigations."

Regarding the 2017 death of Anaya, Alco said they retained an expert who has a PhD in mechanical engineering from MIT who concluded that the equipment had a clear manufacturer design flaw, and that the defect was the sole cause of the accident.

Employees say they don't feel Alco is safe

Caesar Zamora used to work at Alco Iron & Metal in San Leandro.

KTVU spoke to several former employees of Alco.

Only one was willing to go on the record.

"No, it’s not a safe place to work," one former employee said.

He also disputed Alco’s claims that employees are given proper safety training.

New employees, he said, are given some paperwork on how to run machinery, but are never given personal training or even videos on how to work the equipment.

Several of these former employees also claimed that Alco’s safety manager does not regularly patrol the sites to supervise whether work is being done safely or properly. That person seems to only show up after accidents occur, the former employees said.

Cesar Zamora left Alco in 2015, and acknowledges he has a rocky relationship with the Kantors.

"Well, throughout the years that I worked at Alco, I noticed that there was never no certified person training employees for one," he said, adding that many of the employees speak Spanish as their first language. "So, if you put them a paper in front in English, they’re not going to know how to answer those questions. And those questions sometimes can save your life."

He said he and others brought these safety issues to management, but nothing happened.

"You know, we always brought it up because we had a lot of misses," Zamora said. "We had a lot of accidents."

History of violations

In addition to the three deaths, there have been plenty of other accidents and injuries at Alco over the years.

Some examples include a 2016 propane tank explosion on property and a 2012 incident where a worker in San Leandro lost two fingers.

And in 1997, Cal-OSHA fined Alco nearly $300,000 for lead contamination poisoning, issuing 17 "willful" violations when Brown was an inspector.

At that time, Alco employees who worked with lead brought that toxic material back home on their clothing and unknowingly transferred the lead to their children, where the serious health issue was discovered in schools, California Department of Health data shows.

Alco ended up appealing, and getting the violations knocked down to "serious" and paying $24,000 in fines.

"There's nobody who works in scrap metal that doesn't understand that heavy metals, like lead or cadmium, aren't hazards to human health," Brown said. "I mean, it's sort of expecting a nurse not to know that Covid is a problem, or a doctor wouldn't know that Covid was a problem. So, it's ridiculous to assume that somebody who is operating a scrap metal operation wouldn’t know that."

Dangerous workplaces across US

In December 2024, the US Bureau of Labor Statistics published data on how many people died nationwide because of workplace injuries.

There were 5,283 fatal work injuries in the United States in 2023, a 3.7% decrease from 5,486 the year before. The fatal work injury rate was 3.5 deaths per 100,000 full-time workers. In other words, that meant a worker died every 99 minutes from a work-related injury in 2023 compared to every 96 minutes in 2022.

Construction had the most deaths of any industry, with more than 1,000 workers dying, the data showed. The transportation and warehousing sector had second most.

In California, the last three years of available data have shown that roughly 450 people die each year because of workplace fatalities.

What can be done

An overhead shot of the scrap yard at Alco Iron & Metal in San Leandro.

Brown said some things can be done to curb the hazards that occur at companies like Alco, which includes better funding to OSHA, giving the agency more powers.

The most recent state data from late last year shows that Cal-OSHA has 268 authorized, fully funded inspector positions, but only 154 are filled and 114 are vacant. In Oakland, the district office has 12 authorized inspector positions, but there are six vacancies.

Currently, the field enforcement inspector division of Cal-OSHA has a 35% vacancy rate statewide.

California has more than 19 million workers, and Cal-OSHA’s inspector-to-worker ratio is 1 inspector to 120,000 workers. Washington state, for example, has a ratio of 1 inspector to 26,000 workers, and Oregon’s ratio is 1-to-24,000, according to data from the state Employment Development Department and OSHA, which was compiled by Brown.

Because there aren’t enough state workplace inspectors, Brown said the investigations into "bad actors" tend to be "very skimpy."

He did suggest that OSHA’s "High Hazard Unit" be sent in to conduct a comprehensive inspection that would look at the overall health and safety program of Alco’s facility.

"They could do a top-to-bottom review," Brown suggested. "I think that would be an appropriate response."

Remembering Guerrero

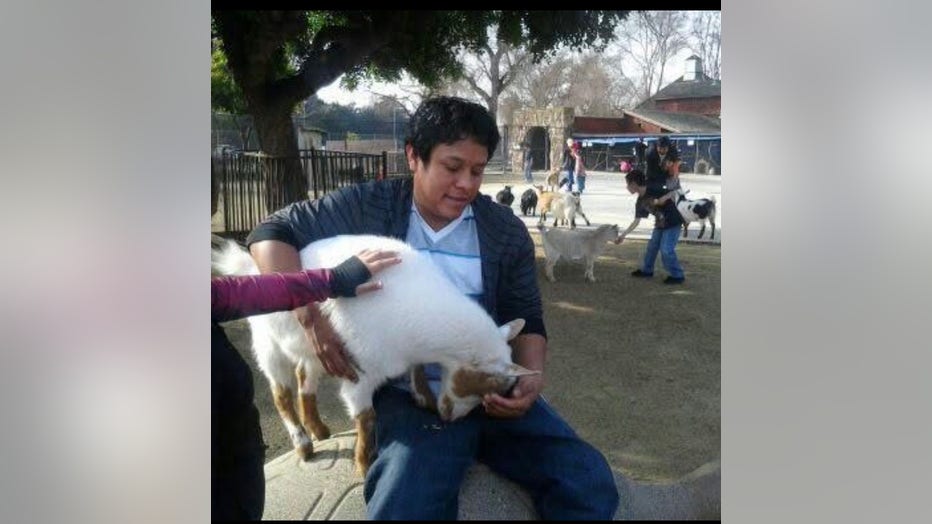

Luis Guerro in an undated photo. He died Jan. 8, 2025, while working at Alco Iron & Metal.

For now, Guerrero’s family and friends are left without him.

"He was a great person to be around," Zamora said. "You would learn a lot from him all the time."

Zamora said he feels terribly for Guerrero’s family, who are now left to struggle financially, and emotionally, without him.

That’s why Zamora said he’s willing to speak out now.

"They’re not taking human life seriously," Zamora said of Alco. "They need to really look thoroughly at their company and see what are they doing wrong. You know, because people can be losing their lives like that. You know, it's just not right. It's not normal."