Bay Area: Life as we know it screeches to a halt

Sirens blare in SF for shelter-in-place

San Francisco police are out, a siren blared early this morning reminding people that there is a shelter-in-place order. Allie Rasmus reports

SAN FRANCISCO - First, people were advised to avoid large gatherings.

Californians adjusted. Life went on. Kids went to school, some people worked from home, but mostly it was business as usual.

Then came the shutdown of almost all California’s schools, and restrictions on smaller and smaller gatherings. The call for bars and wineries to close down.

And finally, about 7 million people in the San Francisco Bay Area were ordered on Monday to shelter at their homes and only leave for “essential” reasons, the strictest measures in America so far, mimicking orders in place already across Europe in a desperate attempt to slow the spread of coronavirus.

Restaurants will be open only for takeout.

All gyms and bars will have to close. Outdoor exercise is fine, as long as people practice “social distancing.”

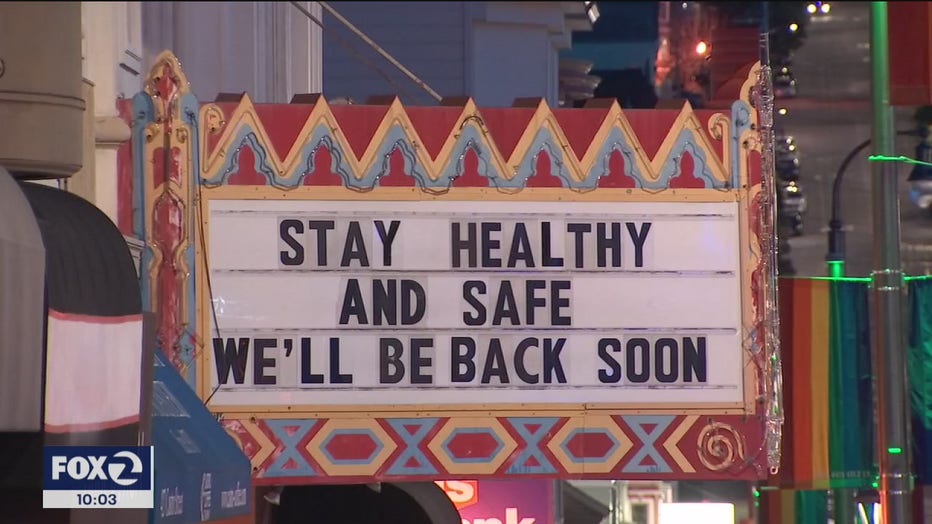

Early Tuesday morning, the first day of the order, San Francisco streets were nearly empty. Sanitation workers were out collecting garbage; the profession is considered essential. A siren blared in San Francisco, a reminder that the order was in effect.

Violating these rules is technically a misdemeanor, though San Francisco police said they will first simply issue warnings.

“You can still walk your dog or go on a hike with another person, as long as you keep 6 feet between you,” said Dr. Grant Colfax, director of the San Francisco Department of Public Health.

It remained unclear if the rest of the state — and country — would follow California’s lead. The nation’s top infectious disease expert, Dr. Anthony Fauci, said over the weekend he would like to see aggressive measures such as a 14-day national shutdown that would require Americans to hunker down to help slow the virus’ spread.

President Donald Trump, asked Monday if he was considering a nationwide lockdown, said, “at this moment, no, we’re not.”

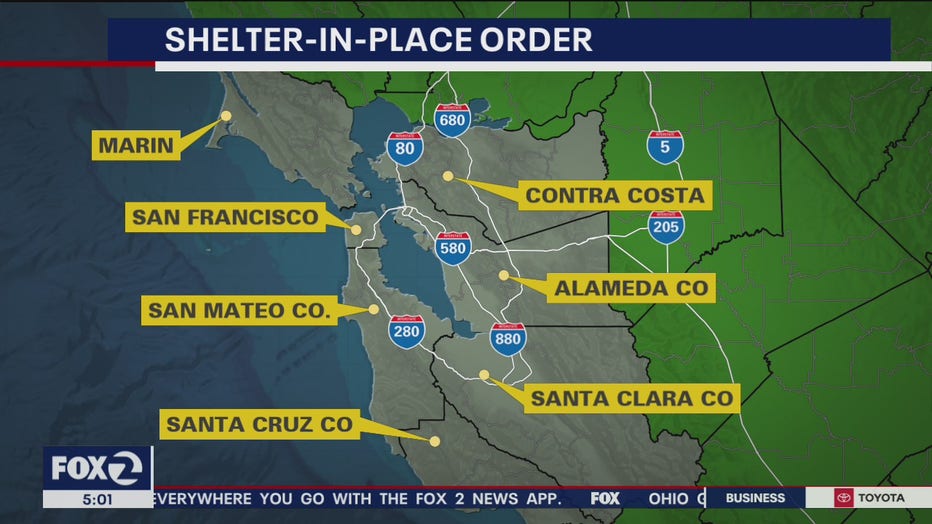

The new order in California applies to about 7 million people living in the counties of San Francisco, Marin, Santa Clara, Santa Cruz, San Mateo, Contra Costa and Alameda. It includes the cities of San Francisco, Berkeley and Oakland.

Speaking in urgent language, officials said the unprecedented directive was based on data that showed a rapid escalation of cases that required quick, bold action to slow down the virus. The order takes effect Tuesday and lasts until at least April 7.

“History will not forgive us for waiting an hour more,” said San Jose Mayor Sam Liccardo, whose city is the most populous in the Bay Area and also the epicenter of the area’s outbreak. “This is our generation’s great test, our moment to stand together as a community. Amid our collective fears, we will find our uncommon courage.”

The dramatic changes have caused confusion and, despite official calls not to panic, no shortage of anxiety.

Across California, and the nation, the scene at supermarkets has been chaotic with lines forming outside before stores open in the morning with restocked shelves. Once open, shoppers jam the aisles and clear out the stock of toilet paper and other paper goods, canned beans, pasta and rice.

The shelter-in-place order set off a new rush. Shoppers in Berkeley flooded into the Berkeley Bowl grocery store after seeing online reports about the virtual shutdown before officials announced it.

“I saw the headline and got this pit in my stomach,” Caroline Park, 38, said as she put on plastic gloves before pushing a shopping cart into the store. “I was going to shop for the week anyway. I’m not here to hoard.”

By 2 p.m., shortly after the televised announcement was made, the line to the store snaked around the block. Store managers shut the entrance to limit the number of shoppers inside.

California’s national and state parks remained open, but many shut indoor spaces, including visitor centers and museums.

A sanitation worker in San Francisco was working on March 17, 2020. He is considered an essential worker

California has confirmed nearly 400 cases of the virus and seven deaths. The virus usually causes only mild or moderate symptoms, such as fever and cough, but can be deadly for older people and those with underlying health conditions.

The order came a day after Gov. Gavin Newsom told all California residents ages 65 or older to stay at home and also called for all bars, wineries, nightclubs and brewpubs to close. Newsom upgraded the orders with more force on Monday.

In Southern California, Los Angeles and San Diego counties — the state’s two largest, with a combined 13.4 million people — ordered bars to close and restaurants to stay open only for pickup, drive-thru or delivery orders.

San Francisco Police Chief William Scott said violating the order is technically a misdemeanor punishable by a fine or jail time but authorities will take a “compassionate, common-sense approach” to enforcement with the goal of keeping the public safe.

The rapid pace of new restrictions — and the emptiness it has prompted in public places — caught people and institutions off-guard.

Kevin Jones, general manager of Buena Vista Cafe, an iconic San Francisco restaurant that has been a draw for tourists since 1952 in the popular Fisherman’s Wharf, said the order is “going to hurt, but our duty is to protect our employees and our customers.”

The cafe was the only one open Monday in one of the city’s busiest tourist areas, and was almost full. He said he’s worried about its 58 employees being able to pay their rent; owners and managers decided any perishable foods would go to the workers.

Near San Diego State University, Will Remsbottom’s Scrimshaw Coffee had just three people, and one was an employee washing windows. “I’m just struggling with this moral conundrum of remaining open and being a potential spreader versus closing and not being able to pay my employees,” he said.

At San Francisco’s infamous Alcatraz, the shutdown closed tours until further notice. Tour guide Manuel Gomez, 49, who supports a wife and two children, said he hadn’t yet come up with another plan to make money.

“It’s devastating,” Gomez said. “We only have enough savings to last us for 10 days.”

KTVU's Allie Rasmus and AP reporters Olga R. Rodriguez and Juliet Williams in San Francisco, John Antczak and John Rogers in Los Angeles, Daisy Nguyen in Berkeley, Amy Taxin in Orange County and Julie Watson in San Diego contributed to this report.