Mental health worse for children with special needs during pandemic

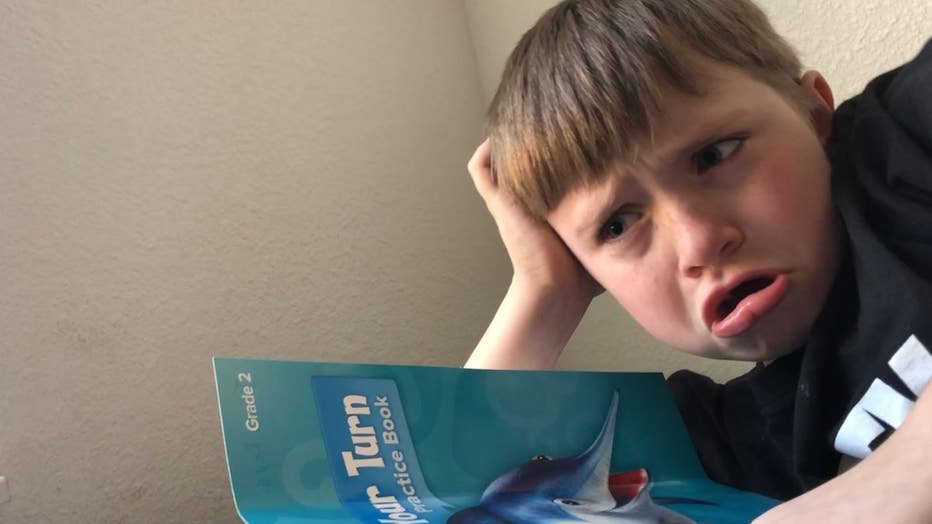

SANTA ROSA, Calif. - For more than a year, 8-year-old Isaac Keys has attended school from his laptop at home. It’s a constant struggle because the isolation and screen burnout has taken a toll on his mental health amid the pandemic. It’s compounded because he has autism.

Psychologists say stress is contagious. Sara Keys knows that all too well as an emergency room nurse. But said trying to teach her son is even more challenging than her nursing job.

"I don’t want to fail him," she said through tears. "I can’t stop trying but I don’t know how to do it and I need the help from the people who know how to do it."

She and her husband have contacted the Sonoma County Office of Education and several school districts attempting to get their son into a social setting with other children with special needs. Repeatedly, they said they received confusing information or were met with roadblocks.

Across the state, in-person learning or intervention for those with learning disabilities is limited. The Keys said they found there are waiting lists and scarce resources.

"The victim is kids like Isaac," his father Chris Keys said. "His behavior now is like we’ve never seen – biting, kicking, flailing, screaming."

And they can’t catch a break. The last time they saw Isaac with this behavior was after their Santa Rosa home burned down in the 2017 wine country wildfires.

It’s that trauma, or other anxieties within family life that research shows can stop education from happening all together.

"Stressed out students can’t learn," said Bay Area school psychologist Rebecca Branstetter. "We’re seeing a lot more children who are struggling with learning."

Data gathered amid the coronavirus pandemic shows depression, anxiety and thoughts of suicide among young people are up. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) said emergency room visits have spiked too.

Before the pandemic, one in five kids had a mental health issue or trouble learning. Brandstetter said now that number is much higher, though data is still being compiled.

Psychologists, whose resources were strapped before the pandemic, are now forced to work at the crisis level.

"Our current ratios are about one school psychologist for 1,500 students," Brandstetter said. "The recommended ratio is about 500 students."

Whether it’s a structured environment, a social setting, or one-on-one attention, every child learns differently.

And when the computer replaces the classroom, experts say some children don’t have the proper supports for their social and emotional needs.

It’s a statewide problem. Despite California guidance allowing in-person schooling for students with learning disabilities, many districts simply don’t offer it.

It has forced hundreds of families to file lawsuits for violating federal law requiring all students to have equal access to the same opportunities for a free and appropriate public education.

"We don’t have enough attorneys to represent all of the families that call us," attorney Gabriela Torres with Disability Rights California said. "There are so many students that are being left behind."

Since last March, the nonprofit has represented hundreds of children with special needs who can’t access education or don’t have the resources needed at home.

Oftentimes, the limitations highlight equity issues exposed during the pandemic. Low-income communities don’t always have the technology access and can’t afford to take legal action against a school district.

In non-affluent parts of the state, school districts lack the funding to better accommodate children with special needs.

"We’re really asking them to focus on the individual needs of each student," Torres said. "Come up with a plan to help address things like learning loss and not accessing education over the course of a year now."

The Keys shared videos with KTVU showing their son’s mental state and focus both pre-pandemic and now.

The ongoing daily stuggle makes them stressed. But moreover, it makes them frustrated that they're unable to get Isaac into a social setting where he'll thrive.

"This isn’t about us getting a break," Chris Keys said. "As long as we’re alive we’ll fight for him so he gets not only what he deserves, but what he needs."

Brooks Jarosz is an investigative reporter for KTVU. Email him at brooks.jarosz@fox.com and follow him on Facebook and Twitter: @BrooksKTVU