Scientists announce discovery of 240-million-year-old 'Chinese dragon'

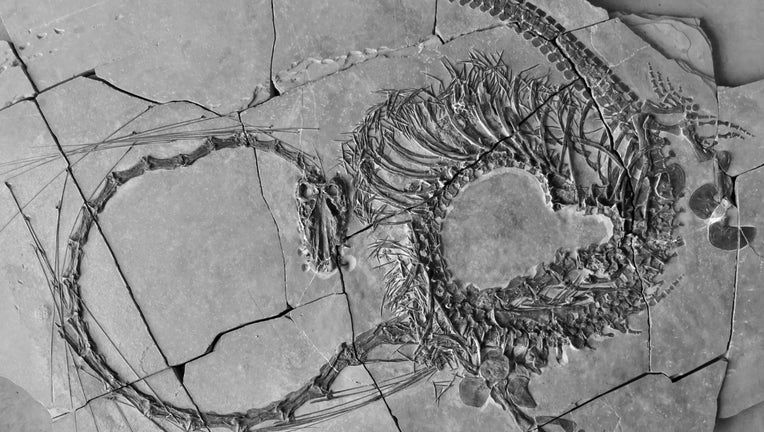

The 240-million-year-old fossil's neck has 32 separate vertebrae, longer than its body and tail combined.

LOS ANGELES - It's only fitting that in the Year of the Dragon, paleontologists would uncover a 240-million-year-old "Chinese dragon" fossil, according to a statement from the National Museums Scotland (NMS) released on Friday.

The fossil is actually a Dinocephalosaurus orientalis, which has a long neck containing 32 separate neck vertebrae, which gives it its resemblance to a mythical dragon.

This isn't the Loch Ness Monster

Researchers note that while there are superficial similarities, Dinocephalosaurus is in no way related to the famous long-necked plesiosaurs that has inspired the myth of the Loch Ness Monster.

The fossil dates back to the Triassic period and was discovered in the Guizhou Province of southern China.

Scientists say the aquatic reptile was "very well adapted" to an oceanic lifestyle. The bones indicate that it had flippered limbs. There were even preserved fish in the region where the animal's stomach would have been.

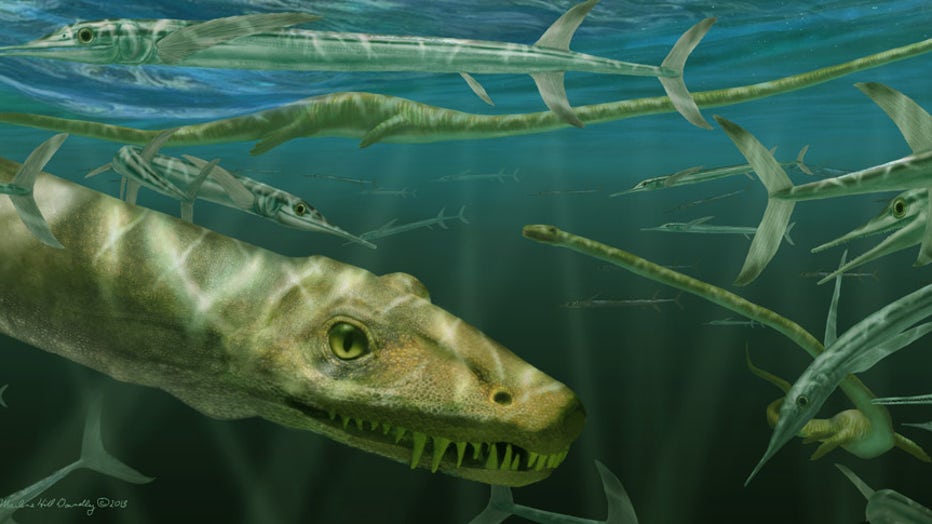

Scientists say the reptile had almost a snake-like appearance.

This particular reptile was first identified in 2003, but this recent discovery allows scientists to obtain a more complete specimen.

A recreation of what Dinocephalosaurus orientalis might have looked like. (National Museums of Scotland)

"This discovery allows us to see this remarkable long-necked animal in full for the very first time. It is yet one more example of the weird and wonderful world of the Triassic that continues to baffle palaeontologists. We are certain that it will capture imaginations across the globe due to its striking appearance, reminiscent of the long and snake-like, mythical Chinese Dragon," said Dr Nick Fraser FRSE, Keeper of Natural Sciences at National Museums Scotland.

An international effort helped discover a "dragon"

It took researchers from Scotland, Germany, America and China to study the fossil.

"This has been an international effort. Working together with colleagues from the United States of America, the United Kingdom and Europe, we used newly discovered specimens housed at the Chinese Academy of Sciences to build on our existing knowledge of this animal," said Professor Li Chun from the Institute of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Palaeoanthropology.