Figures suggest pandemic has accelerated enrollment declines facing California school districts

OAKLAND, Calif. - The pandemic has accentuated and accelerated an already major concern about student enrollment in California schools, prompting state experts to urge school districts to act now to avert a looming fiscal cliff.

The state, which has long been dealing with a downward trend in enrollment, saw a notable drop of more than 160,000 enrolled students last year from the previous school year, a decline of 2.6%.

And figures projected the next decade will see an 11.4% decline from pre-pandemic figures. "...a further decline of 542,200 in total enrollment is projected, resulting in total enrollment of 5,460,300 by 2030-31," according a forecast from the California Department of Finance.

State figures showed the largest increase was projected in San Joaquin County, forecast to gain 6,100 students in that ten year period.

Coastal counties and parts of the Bay Area were among the regions that were expected to be the hardest hit, according to an analysis by EdSource.

It's a trend felt by many Bay Area school districts that have seen enrollment numbers fall and in turn has had to deal with millions of dollars in losses over attendance-based funding by the state.

Figures released to the San Francisco Unified School District’s Board of Education last week showed the district has lost more than 2,400 students this school year compared to last with enrollment declining 6.6% since fall of 2019. The declines were most pronounced in the early grades from transitional Kindergarten through 3rd.

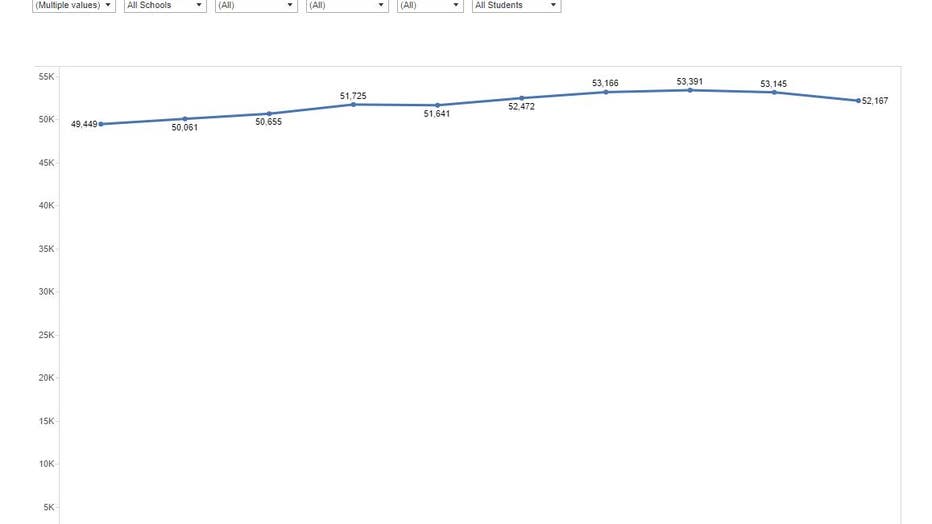

In Oakland, more than 1,200 students have left the district since the 2018-2019 school year, when overall enrollment stood at 53,391.

(Oakland Unified School District )

In Sonoma County, the figures were more drastic as there was a loss of more than 3,200 students from pre-pandemic figures, when enrollment stood at 69,734, according to the California Department of Education.

For many districts, the pandemic’s impact on enrollment came amid a perfect storm.

"Early indication from school districts is that we’ve seen a fairly dramatic decrease since last year that we thought in part would be one time in nature, but appears to be recurring this year," explained Michael Fine, CEO of the Fiscal Crisis and Management Assistance Team, an external state agency that assists school districts dealing with financial challenges.

The agency has worked with Bay Area school districts including Oakland Unified and has recently been called in to help the San Francisco Unified School District with its fiscal troubles.

SEE ALSO: Facing teacher shortage, San Jose Unified counselors substitute in classrooms

Fine said that prior to the pandemic, there were 50 percent or more districts across the state that were struggling with declining enrollment. "But during the pandemic that number has accelerated," he noted, adding, "We’ve been in a long period of decline, however this is the first year that the state has experienced a negative growth in population."

SEE ALSO: California reports first ever yearly population decline

That’s among a myriad of demographic factors that have been steadily contributing to fewer kids enrolled in California schools.

"You've got population decrease, you’ve got birth rate decrease, right now because of the pandemic you have death rate increases," Fine explained.

And he pointed to research that showed residents were delaying or waiting to have families.

"Number one, college going rates are going up. When college going rates go up, people delay having families," Fine said, adding, "That's a good thing. That's a direct result of good work we’ve done in K-12 schools."

Also another direct result of education, according to Fine, were dramatic declines in teen pregnancies.

And then there were young adults holding off on having kids because of California’s high cost of living and housing.

SEE ALSO: Poll: Majority of Bay Area residents say they're likely to leave the region in next few years

"So all that delays families. It doesn't necessarily mean that folks won’t have school kids and put them in their public school, but there’s a delay to it. You’ve got a period of time of these shifting demographics," Fine said.

So given these trends, Fine stressed that districts need to act now. "We describe the next years as a fiscal cliff," he said. "You know the stars are all kind of lining up."

And while he said it was still early to suss out the specifics on how the pandemic has contributed to the decline, one pandemic related factor that's expected to contribute to the "fiscal cliff" was the looming expiration of state and federal COVID relief aid. Districts will find themselves without that assistance and will have to adjust.

According to Fine, those adjustments should look different from district to district depending on the local reasons for what's leading to the enrollment declines, as he said it boils down to three things: districts knowing their data and what’s happening around them; evaluating the local impact and understanding what the loss means to revenue and on their own operations; and then executing to make decisions based on all the factors.

And he urged not waiting to take action. "The earlier you make those decisions, the less painful they are," he said, while stressing that lay-offs shouldn’t be the first reactive action, though he noted that in some situations a district might not be able to get around it.

SIGN UP FOR THE KTVU NEWSLETTER

"I don't jump to lay off especially in the current environment where we’re struggling to hire people," he said. "Layoffs are very disruptive… Although in big numbers layoffs is what have to be considered, more importantly what has to be considered is staffing levels. And in some districts, normal attrition will solve that."

The full extend of how the pandemic has affected the state's latest enrollment won't be known until about March when the Department of Education was expected to processes the official data.