San Francisco's Black population is dwindling, but one radio station remains community stronghold

KPOO 89.5 FM studio San Francisco. (Photo courtesy Charlie P. Miller)

SAN FRANCISCO - The sound of Barbara Gainer’s voice comes through loud and clear on the radio every Tuesday morning from 9 a.m. to noon. Like clockwork, listeners can count on her familiar warm timbre when she delivers the repetitive trademark line, "You’re listening to grown folks, grown folks, grown folks music." And then she plays her own special blend of jazz and blues.

The disc jockeys at San Francisco’s KPOO-FM 89.5 are not just unique voices who play soul, oldies, reggae, salsa, gospel, hip hop and deliver the news. They’re a source of comfort.

These programmers are characters, personalities and people who are looking to connect with their audience; something that has proven to be that much more important during the coronavirus pandemic. When life as we knew it upended, we wanted to cling to structure and stability -- live radio can offer just that.

The station’s evolution dates back to 1970, when a scrappy radio engineer with a dream, Meyer Gottesman, applied for an FCC license to construct a radio station. Originally the call letters were set to be KPPC, to stand for the nonprofit Poor People’s Radio Inc., which founded the station. That was quickly changed to KPOO supposedly for aesthetic reasons. However, you should not pronounce it ‘kay-pooh’, especially on the air.

The original intent was to have a station dedicated to poor people. Fittingly, the FCC initially denied the license application because they didn’t think the founders would have enough money to operate.

In a recent interview on KPOO, Gottesman said back then, the FCC gave community broadcasters educational requirements. "You simply couldn’t be a free-format station in those days." In his words, they were just, "plain folks who wanted to broadcast."

KPOO wouldn’t actually go on air until 1973. That was the year Charlie P. Miller, host of Sunday night’s eclectic oldies mix, ‘The Autumn King Show,’ started broadcasting at the station. He explains how the station’s original management was petitioned by a new faction of community members under the argument KPOO should be Black-operated. With an agreement in place, the station’s operations were transferred over and its first board was created in 1974.

After finding its first home at Pier 46A, the station settled on Divisadero Street in the ‘80s, where it has since broadcast from the Western Addition neighborhood. Miller describes their second unassuming Divisadero studio as "funky" and "well-worn" and that "the equipment works most of the time." The elder resident DJ spins vinyl, cds and has adapted to the digital age by bringing in his obscure soul and oldies tracks on a USB memory stick.

Despite San Francisco’s dwindling Black population, KPOO has remained a community stronghold on the dial and still serves its purpose by providing noncommercial, free-format radio.

For Lamont Bransford-Young, aka DJ Lamont, as Tuesday slips into Wednesday’s wee hours of the morning, he typically packs 50 vinyl records into his bag as he prepares to spin house, disco and NuJazz music for his show, the ‘Fingersnaps Music Salon’. He’s amassed his collection since he was 14. Now at 56, he says the station is a place to share his life as a gay Black man.

"There is no Black gay voice in electronic media in San Francisco," he says. "We don’t have a Black gay electronic outlet. We have no presence. Me on the air gives us identity. We’re alive and well."

He’s also referring to the statistic that the city’s Black population has hovered at around 5% or less for the past 10 years.

Asked to identify the station’s current listening demographic he says, "It’s hard to say because we are a nonprofit." At community events the station would throw pre-pandemic, he says that "old school SF and elders" would show up.

Boom Boom Room, the historic Fillmore District blues club founded by John Lee Hooker, is a longtime supporter of the station. They have helped KPOO fundraise in the past. Sadly, the music venue planted in an area steeped in jazz and once known in a bygone era as "Harlem of the West," has had their own struggles in keeping afloat due to the pandemic.

By the 2010s, an influx of tech money and workers displaced many neighborhood fixtures in the Western Addition. What was historically a Black neighborhood rapidly gentrified as the corridor became almost unrecognizable. It was rebranded NoPa (North of the Panhandle).

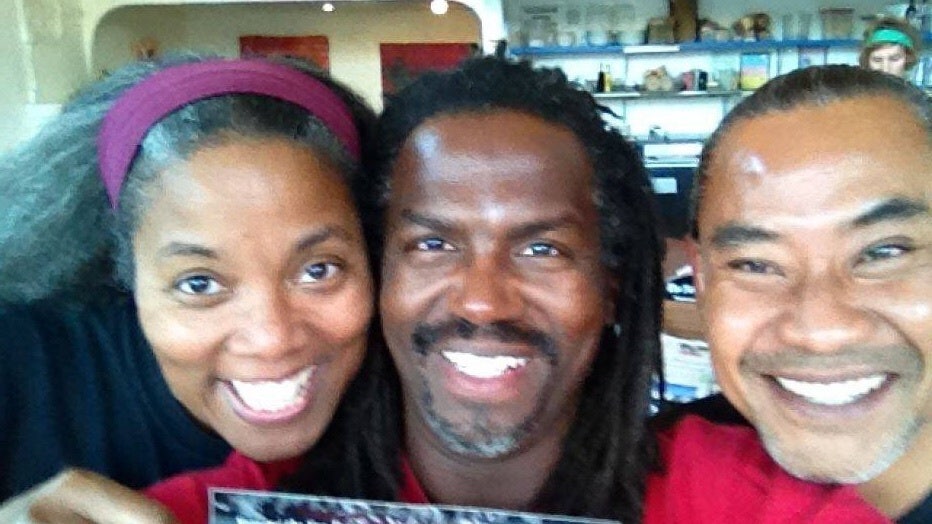

DJ Marilynn. DJ Lamont. KK Baby (Photo Courtesy: Lamont Bransford-Young)

"We’re still here," Marilynn Fowler says, reverberating Bransford-Young’s sentiment. She’s been a volunteer DJ at the station since 1988 and has a say-yes-to-everything attitude.

Fowler, a San Francisco native, noticed a shift in the city in the mid 2000s. "The community is getting smaller and smaller." She recalls a daytime walk near Dolores Park from around that time. "I didn’t really think about walking down the street. I realized the people ahead of me were walking faster because they were nervous. That didn’t used to happen." She says their body language was a reaction to the color of her skin.

Fowler ended up in community radio by accident. She has a background in musical theater and choreography that includes affiliations with Thrillpeddlers’ Hypnodrome Theatre, Box Dance Troupe and Sick and Twisted Players.

When a job she had worked at shut down, she had some free time on her hands. She called the station looking for an opportunity and the station’s general manager at the time, Joe Rudolph, answered. Fowler impersonates his gruff voice in recalling that conversation. "Can ya type?" he asked. She groaned. But as fate would have it, when she did end up at KPOO, that led to an on-air DJ teaching her how to cue up records, which led to Rudolph barking, "Well, the DJ is leaving. You wanna go on air?"

The station used to broadcast SF Board of Supervisors meetings. She was told they never go in closed session and they never end early. But that day, with Fowler in the booth, they did both, setting off a broadcast panic. In a sink-or-swim moment, her first on-air shift lasted almost five hours to fill the void left by the supervisors' meeting.

Now she has two shows on Monday, ‘The Power of Blues Compels You’ and an interview show, ‘Let Me Touch Your Mind’ where she employs a naturally inquisitive interview style. She was the one who interviewed Gottesman, and credited him as the station’s first president and founder. She mostly interviews scientists and artists, or those in the realm of arts and culture, and has talked about her appreciation for burlesque and drag.

Like Fowler, Bransford-Young is no stranger to feelings of isolation. His experience of sharing music and connecting to his audience is deeply personal. He says through the airwaves, he can be himself.

"I felt like a loner when I was a teen. I felt unheard and unseen, and music filled that space," he explains. "I used to listen to the radio religiously. [It was] not a pastime, not a hobby. It fulfilled a space."

Bransford-Young has been at KPOO since 2010. He talks on the air vulnerably about his experience, about molestation, his own fears, and his husband. "I can speak about them openly, which in turn will free me later," he says.

KK Baby. DJ Lamont (Photo Courtesy Lamont Bransford-Young)

He tries not to preach, but his tagline reads like a refrain: "Create something beautiful for yourself and others." This uplifting encouragement is his cathartic natural expression. "We can self-indulge," but to him sharing is more meaningful.

His on-air tone is sensitive, relatable, and conversational. He talks about walks in parks and other things he enjoys doing in the city. He says the music flows through him throughout the night. Some of his go-to disco and house tracks are "Deeper Love" by Ultra Naté from 1989. "I play that a million times." Change’s "Hold Tight" and Sylk 130’s "Seasons Change" the Philharmonic house mix that came out 20 years ago.

"European DJs get all the credit, but it was Black gay kids who made this music and celebrated it. For the Black queer artists to get credit for this normally doesn’t happen unless it was a special segment or a certain time of year," he says with a keen sense of awareness. "The dance music I play has cultural significance. African house music has unique linguistic and cultural influence from another land. It reminds us to be more than you think you are. To dream, imagine and hope."

In between tracks he’ll ask on air, "How are you today? How does it feel to be home now that you’re home 24 hours a day? What do you do when you don’t like your roommate anymore?"

In keeping with the station’s tradition of service to low-income communities and its mission of opening the airwaves to the disenfranchised and underserved, Bransford-Young is conscious of his listeners.

"When I produce my show. Someone is at home or in their environment. In their tent. Radio is a very personable medium. It’s active and passive," he says. "For the few people I’ve met during the pandemic, they have said, ‘You are a calm in this storm. We can depend on you.’"

Fowler elaborates on the symbiosis of the DJ-listener relationship.

"When the pandemic hit. I was filled with anxiety," she says. "When we had to go in lockdown mode on March 16, being able to go into the station gave me purpose."

She says she is gratified by doing her part even if they are small things.

"I could walk to the station and say, ‘Here’s food pantries, eviction information, COVID testing'. I can’t do much, but I can do this," she says.

Even the DJs aren’t exactly sure how KPOO, or radio in general for that matter, fits into the changing landscape of San Francisco in 2021 or what the future holds. The internet age, and apps like Spotify, Bandcamp, Soundcloud and YouTube have been disruptors.

But live, terrestrial radio is something special; an art form flowing freely through the airwaves. No app or Bluetooth speakers necessary, no phone battery to charge and available at the push of a button.

"Anyone can have a podcast," says Fowler. "If you want to keep something alive, you have to have fresh blood. The way to keep it alive is to get young people involved and interested. Any medium connected to art young people are doing is going to survive. If all the people you have are aging, it’s going to die with you."