Fusion ignition at Livermore lab advances clean energy solution

Clean, safe nuclear energy seems possible after scientific breakthrough

Scientists at the Lawrence Livermore Laboratory say they have successfully produced nuclear fusion with lasers. Such a discovery suggests that one day this process could be the source of a clean, safe energy that helps reduce reliance on fossil fuels which cause climate change.

LIVERMORE, Calif. - Scientists are one step closer to developing a never-ending clean power source that is free of nuclear waste.

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory researchers created a nuclear fusion reaction last week that for the first time, produced more energy than was used to ignite it.

The major breakthrough was announced Tuesday by U.S. Department of Energy officials, following the nearly 60 years attempt to harness what powers the sun and stars.

"We have taken the first tentative steps toward a clean energy source that could revolutionize the world," said Under Secretary of Energy Jill Hruby.

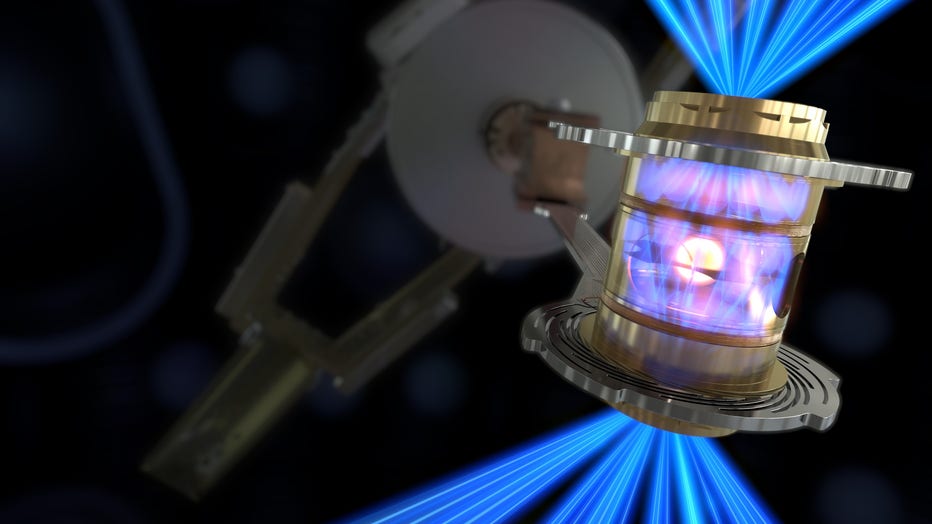

At the National Ignition Facility at the lab, 192 lasers shot into a cylinder the size of a pencil eraser and squeezing hydrogen atoms with such precision they combine and ignite.

Fusion ignition results in what is known as a net energy gain, creating more energy than the lasers used.

"It took a while to sink in that we had finally gotten over this hurdle," said lead experimentalist Alex Zylstra. "It’s really gratifying."

The process happens at high temperatures and pressures, making it very difficult to control.

Scientists spent weeks planning for the shot and said they tweaked the output of the lasers that resulted in the net energy gain.

"These are really extreme conditions," Zylstra said. "The temperatures, densities and pressure we achieve are higher than at the center of the sun."

Advocates say it could one day replace fossil fuels by producing carbon-free energy that powers homes and businesses and leaves behind no nuclear waste. Fusin could also solve clean energy storage issues found with solar and wind power.

"This is the ideal complement to clean, renewable energy storage," UC Berkeley Professor of Sustainability Dan Kammen said. "It allows you to think of fusion as a baseload partner, not a competitor but a real partner with clean energy going forward as we need to meet these mid-century targets of zero emissions."

Long term it’s seen as a potential solution to fighting climate change.

But harnessing and creating never-ending clean energy is still a decade or more away.

There’s still a long list of engineering hurdles before scaling and manufacturing fusion power technology could happen and power plants built.

"Now we need to simplify and strip away the engineering to find out what do we need to make at the minimum to make this work," Kammen said. "That’s what’s going to excite graduate students. It’s going to excite Silicon Valley startup companies. It’s going to get the really competitive, innovative juices flowing."

Brooks Jarosz is an investigative reporter for KTVU. Email him at brooks.jarosz@fox.com and follow him on Facebook and Twitter @BrooksKTVU