K-9s in question: Bay Area police dogs bite with little consequence

K-9s in question: Bay Area police dogs bite with little consequence

Police dog bites can cause severe injuries but there has never been any legislation proposed or passed in California to regulate K-9s. In the Bay Area, San Jose police lead the pack with the most number of dog bites.

MOUNTAIN VIEW, Calif. - Joel Alejo was taking a nap in the backyard of his family’s Mountain View home when he was startled awake by a German shepherd's teeth piercing his right leg.

The attack, he said, seemed to go on forever.

"Dersh! Dersh! Dersh! Deeerrrsh!" the dog’s Palo Alto police handler cried, compelling the animal in its native Czech to bite again and again.

"I’m still shaking to this day," Alejo told KTVU in a recent interview, as he remembered the June 2020 attack that left him physically and emotionally scarred.

The episode turned out to be a grievous error by law enforcement who were searching for a kidnapping suspect – but stumbled upon an innocent man.

The dog bite cost taxpayers $135,000 in a civil court settlement and left Alejo with wounds that still cause him pain.

It’s cases like Alejo’s that have critics horrified and have prompted calls to restrict – or even abolish police K-9s from biting – altogether.

"Outside the firearm, there is no police tactic that is as likely to cause injury and is likely to cause serious injury as a police dog – nothing else comes close," said Don Cook, a California attorney who’s handled hundreds of dog bite cases.

Law enforcement agencies across the country rely on K-9 units – and their sophisticated noses – to find missing people, sniff out explosives and help rescue stranded victims trapped inside hard-to-find places.

The dogs also apprehend suspects who, police say, are resisting arrest or committing dangerous, high-risk felonies that could endanger officers if they try to go hands-on.

Graphic photos: Police K-9s cause serious injuries throughout the Bay Area

Joel Alejo of Mountain View is still haunted by being attacked by a police dog.

But police dog bites can also cause severe, long-lasting injuries and prompt costly excessive force lawsuits. The most commonly used dogs, German shepherds and Belgian Malanois, bite with force that can crush bone.

Officers are rarely held accountable in controversial cases, and records show that canines are disproportionately deployed on Black and Hispanic people. Sometimes people are bitten when they are not suspected of a violent crime – or like in Alejo’s case – no crime at all.

And even as California has recently adopted a variety of use-of-force reforms following a national reckoning around police accountability, K-9 use has remained largely unregulated on a state level.

"If the officer, him or herself, tried to do what a police dog does, the officer would get fired, practically on the spot" Cook said.

Investigation into dog bites

A two-month KTVU investigation analyzing K-9 bite data among the Bay Area’s 25 largest police departments revealed major discrepancies between agencies. Some departments routinely deploy police dogs to bite suspects while other similar-sized departments virtually never use them.

The investigation found San Jose police lead the pack with 167 bites over a five-year period.

Richmond police had the second most bites – 84 in the same time period.

And in Antioch, a smaller city with fewer than 100 officers, police dogs bit people 49 times in just three years. One dog was responsible for 22 of the bites.

By contrast, in the San Francisco and Oakland police departments – both of which have been under years of police reforms that include restrictive use-of-force policies – K9s bite people less often.

San Francisco recorded just two bites in the past five years, while Oakland documented 13 bites over the same period.

Officer Steven Aponte, a San Jose police spokesman, addressed his department's statistics in a statement to KTVU. He stressed that when possible, officers attempt to deescalate situations before using dogs and that "we take these uses of force and subsequent investigations very seriously."

The varying numbers are likely influenced by factors like crime rates, size of the police jurisdiction and the number of K-9s each agency has.

But critics say use-of-force policies have the biggest impact on how often dogs bite.

"Each department can set its own rules, or no rules at all," said Bay Area civil rights attorney John Burris.

The city of Berkeley opted against K-9s in the 1970s to avoid all the trouble that comes with them, said East Bay civil rights attorney Jim Chanin.

It’s a rare exception.

Most major Bay Area law enforcement agencies have apprehension K-9 units that subdue suspects with their jaws.

KTVU’s investigation found there are no uniform standards dictating when a police officer can deploy a dog and how long a dog can "stay on the bite." For instance, a dog can bite someone for an entire minute – something that is OK within most departmental policies.

The Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training – or POST – sets training standards for California law enforcement, but requires no certifications for police K-9s; only recommendations on best practices.

A review of state records shows there has never been any legislation proposed or passed in California to regulate K-9s and that discipline for officers is rare.

KTVU reviewed nearly two dozen serious dog bite injury cases in the Bay Area and officers were found to have violated policy in only three of the instances.

By the numbers: How often Bay Area police agencies deploy K-9s to bite

A KTVU investigation found that San Jose police dogs lead the pack of bites in the Bay Area.

Police dogs bite ‘because they can’

In the Bay Area, many departments have a "find and bite" policy, allowing police to use dogs to search for and bite people simply if they’re suspected of a felony. The standard is much looser than other use-of-force options – like batons or Tasers – which often require an imminent threat of harm before they can be used.

Critics say such policies on K-9s use allow police to disproportionately use violent force against some suspects.

"Police dogs bite because they can," said Ernest Burwell, a former Los Angeles County Sheriff K-9 handler who now serves as a national police dog expert and critic. "There are no laws stopping it."

He pointed out that police may not use any other weapon for an unlimited, extended time.

"Why is a K-9 allowed to bite indiscriminately?" Burwell said.

KTVU’s investigation also found that Blacks and Hispanics were bitten by police dogs in two thirds of the cases where race and ethnicity were tracked.

Burris said the numbers point to racial bias. He added that police dogs in general evoke the disturbing imagery of violence against Black protestors in the South during the Civil Rights movement.

"It should be looked at as a racial profiling question," he said.

But retired Los Angeles Sheriff’s Cmdr. Sid Heal says most people who are bitten are violent suspects who refuse to surrender and K-9s are often released before police even see the suspect.

"We have no idea, is this guy male, female, black, white, large, small?" Heal said. "All we know is he’s been involved in a violent crime. We only find out afterwards that he is Hispanic or White or Black."

Troubles with police dogs are not unique to the Bay Area.

More than 32,500 people were taken to emergency rooms from K-9 bites across the country from 2005 and 2013 and 42% of them were Black, according to a 2019 study by Indiana University School of Medicine.

And in 2020, the Marshall Project and partner newspapers looked at 150 serious dog bite cases around the country, which found numerous controversial cases and wide racial disparities.

Talmika Bates is still suffering from PTSD-like symptoms after her scalp was ripped off by a Brentwood police dog.

Disturbing case in Brentwood

The K9 bite issue was reignited recently in the Bay Area when a German shepherd in Brentwood named Marco ripped Talmika Bates’ scalp off.

The woman had fled police after stealing thousands of dollars of perfume and makeup from an Ulta beauty store in February 2020.

The driver of a getaway vehicle she was riding in rammed a police cruiser before the suspects fled on foot into a field.

Body camera video showed the dog biting Bates for nearly one minute as she hid in a bush. She was given no time to come out.

The K-9 handler acknowledged in police reports that he gave no warning because he didn’t know the 24-year-old woman had been hiding in the bushes.

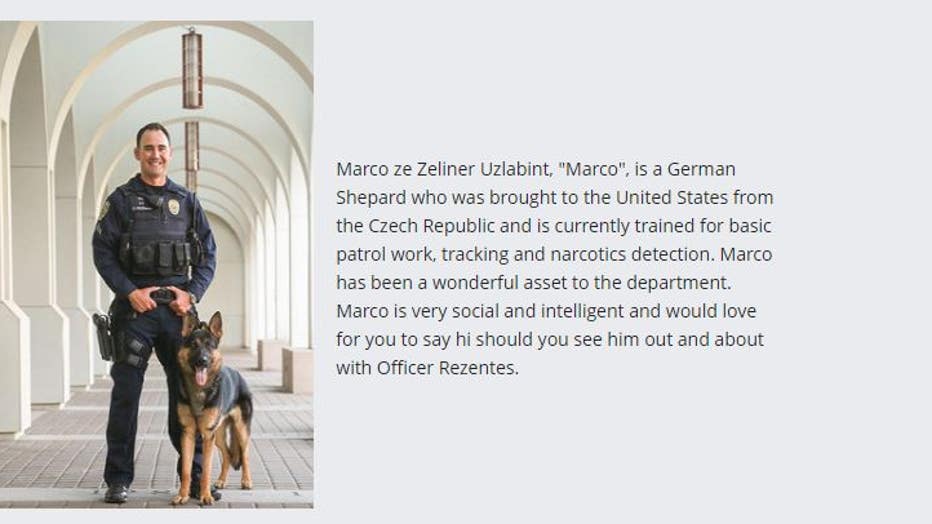

Marco and Brentwood Police Officer Bryan Rezentes.

Her crime at the time was a felony, which allowed Rezentes to send in the dog, even though she was unarmed.

City records show the officer followed policy and was not disciplined despite the horrific injuries Bates suffered.

The city of Brentwood had promoted its dogs on the police department's website, but took down any reference to the K-9 unit shortly after KTVU's story.

One year earlier, Rezentes sent Marco into an attic crawlspace to search for a woman with a prior violent felony.

She was unarmed and the dog bit her in the head as well. The department found the officer acted within policy.

Critics say canine use-of-force cases would cause more public outrage if officers were using any other weapons.

"Could a cop take a knife to her skull and take her scalp off?" Cook asked. "Of course not. But as soon as it’s the dog, people say, ‘What can you expect from a dog?’"

He said that attitudes around police canine use have begun to change with the plethora of cell phone and body-camera video showing the attacks in graphic detail.

K9s can assist police in searches for missing people.

Police believe K-9s can keep them safer

But former K-9 handlers, such as retired Oakland police Lt. Jeffrey Loman, say canines can be an important tool for officer safety – if they’re used properly.

He worked with K-9 Nicko during the city’s most violent years in the 1990s when the crack epidemic spurred a surge in shootings and homicides.

"Having a K-9 was especially useful when we were looking for a particular shooting suspect, homicide suspect, robbery suspect," he said. "Our ability to rapidly search a particular area while allowing our officers to remain safe became of paramount importance for our department."

Loman, though, believes departments should have strict policies around K-9s, so they’re used as intended.

"I don’t think that officers should indiscriminately use their dogs just because somebody meets the definition of a felony," he said. "We should look at the totality of the circumstances."

Critics disagree

Other critics like Cook, though, question whether K-9s perform as intended.

He said releasing a dog on a violent suspect will often escalate the situation. It flies in the face of more modern police policies that focus on deescalation, he said.

"A dog bite provokes a violent reaction," he said. "It makes it more likely that the officer is going to be involved in some kind of physical confrontation and makes it more likely that if the suspect has a weapon – such as a gun or a knife – that he will use it."

There has been no legislation proposed or passed in California to regulate police dog bites.

Police dogs can bite the wrong people, or those suspected of minor crimes

A review of about two dozen cases in the Bay Area – especially those in excessive force litigation – show that in many cases, police send their K-9s to bite when people are suspected of committing minor crimes.

Ali Badr was attacked by a K-9 named Dexter in San Ramon after the Uber driver missed a rental payment on his car. Police conducted a high-risk felony stop in December 2020 and let the dog loose on him. Badr underwent three surgeries and is now suing the city.

Richard May was bitten by a San Mateo County sheriff’s K-9 for trespassing in 2015. May, then 64, had been trying to rescue his 73-year-old neighbor’s cat that had hopped over a fenced construction site. The deputy ordered his dog to attack May, which bit him multiple times in both legs. The attack lasted roughly a minute. May was awarded $1.1 million.

And the investigation found that at times, police sic their K-9 on the wrong person, like Adam Gabriel.

In June 2021, Sonoma County sheriff’s deputies released their K-9 on Gabriel, a Marine Corps veteran, whom they mistakenly thought stole a green Subaru. The dog bite punctured Gabriel’s bicep and there was significant internal bleeding. Deputies later acknowledged Gabriel was not the carjacker. He's sued the sheriff.

A Palo Alto police dog was commanded to "Dersh," or bite Joel Alejo.

In Alejo’s case, an independent police auditor found the dog’s handler, police Agent Nick Enberg, failed to announce himself before going into the backyard.

Even so, an internal review determined Enberg was justified in ordering the dog to bite – despite the fact that he was innocent of any crime.

And years later, because of legal and bureaucratic delays, Alejo still hasn’t seen any of the comparatively modest $135,000 he was awarded in his settlement.

Alejo was out of work doing construction for several months while he healed. He still has large scars on his right leg.

He spoke to KTVU hoping his story would provoke a closer look at how departments use police dogs and the long-lasting impacts of a bite on a real human being.

He said he gets frightened whenever he hears or sees a dog.

"Anytime I hear a dog bark – I'm jumping," Alejo said.

Evan Sernoffsky is an investigative reporter for KTVU. Email Evan at Evan.Sernoffsky@foxtv.com and follow him on Twitter @evansernoffsky. Lisa Fernandez is a reporter for KTVU. Email Lisa at lisa.fernandez@foxtv.com or call her at 510-874-0139. Or follow her on Twitter @ljfernandez.